Agents are fast. You're responsible.

If you’ve been shipping software for a while, you’ve seen this movie: memory management got abstracted, compilers got smarter, the web happened, containers happened. Each wave has people who already onboarded and are running - and people who are skeptical, didn’t have time, or are stuck trying to figure out what the “right” workflow even looks like.

Agentic coding is the same. The tool is real. The manual is… crowd-sourced.

November 2025: The Inflection Point

The CLI agentic tools started appearing in early 2025. Claude Code launched in February as a research preview. Cursor shipped agent mode. OpenAI released Codex CLI. Aider had been around since 2023, quietly building a following. The tooling was ready.

But the models weren’t there yet. If you tried these tools in early 2025, results were hit-or-miss. Agents would confidently produce code that didn’t quite work, hallucinate APIs, or get stuck in loops. Andrej Karpathy captured the sentiment many developers felt: agents “just don’t work” because “they don’t have enough intelligence, they’re not multimodal enough” and “they’re cognitively lacking.” For many, autocomplete was the sweet spot - anything more autonomous felt like a dead end.

Then November 2025 happened.

Within weeks of each other, three major model releases landed: Claude Sonnet 4.5 (late September), Gemini 3.0 (November 18), and Claude Opus 4.5 (November 24). GPT-5.2 followed in December. These weren’t incremental improvements - they crossed a threshold. The models could reliably understand context, make coherent multi-file changes, recover from errors, and complete agentic workflows end-to-end.

The CLI tools that had been waiting for capable models suddenly had them. The shift happened, but it took a few weeks for people to notice. Most of us, myself included, only realized somewhere around Christmas that we had something fundamentally new in our hands. Not “better autocomplete” - a different tool entirely.

By the time the holidays ended, the reactions from people who’ve been writing code for decades started pouring in:

"It does not matter if AI companies will not be able to get their money back and the stock market will crash. All that is irrelevant, in the long run.... Programming changed forever, anyway."

— Salvatore Sanfilippo, creator of Redis

"Software engineering is radically changing, and the hardest part even for early adopters and practitioners like us is to continue to re-adjust our expectations."

— Boris Cherny, author of Programming TypeScript

"Clearly some powerful alien tool was handed around, except it comes with no manual and everyone has to figure out how to hold and operate it while the resulting magnitude 9 earthquake is rocking the profession. Roll up your sleeves to not fall behind."

— Andrej Karpathy, former Tesla AI Director

"LLMs are going to help us to write better software, faster, and will allow small teams to have a chance to compete with bigger companies. The same thing open source software did in the 90s."

— Linus Torvalds

"I don't want to be too dramatic, but y'all have to throw away your priors. The cost of software production is trending towards zero."

— Malte Ubl, former Google engineering lead

If you’re still skeptical, you’re out of step with where a lot of serious builders already are. The people above aren’t easily impressed, and they’re not selling anything. The shift is already underway. The question is whether you’ll adopt it intentionally or accidentally.

The Agent Loop

Forget magic. An agent is a while loop.

You give it a goal. It calls an LLM. The LLM either produces a response (done) or requests a tool call (read a file, run a command, make an API request). The tool executes, the result goes back to the LLM, and the loop continues. That’s it. No neural networks communicating telepathically. Just a loop.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

while True:

response = llm.call(context)

if response.has_tool_call:

result = execute_tool(response.tool_call)

context.append(result)

else:

return response.text

If you’ve written a CI pipeline, a bash script that retries on failure, or a REPL - you already understand this. Same pattern: automated execution with feedback. The difference is the decision-making happens via LLM inference rather than hard-coded if statements.

All major vendors document this loop explicitly:

- Anthropic’s How Claude Code works describes it as a “single-threaded master loop” -

while(tool_use) → execute → feed results → repeat - OpenAI’s Codex agent loop documentation walks through the same pattern

The industry converged on this design because it works. Simple and debuggable.

“Isn’t this just Copilot with extra steps?” No. Copilot predicts your next few characters. Agents execute multi-step workflows - refactoring across files, running tests, fixing failures, iterating until tests pass. Different category entirely.

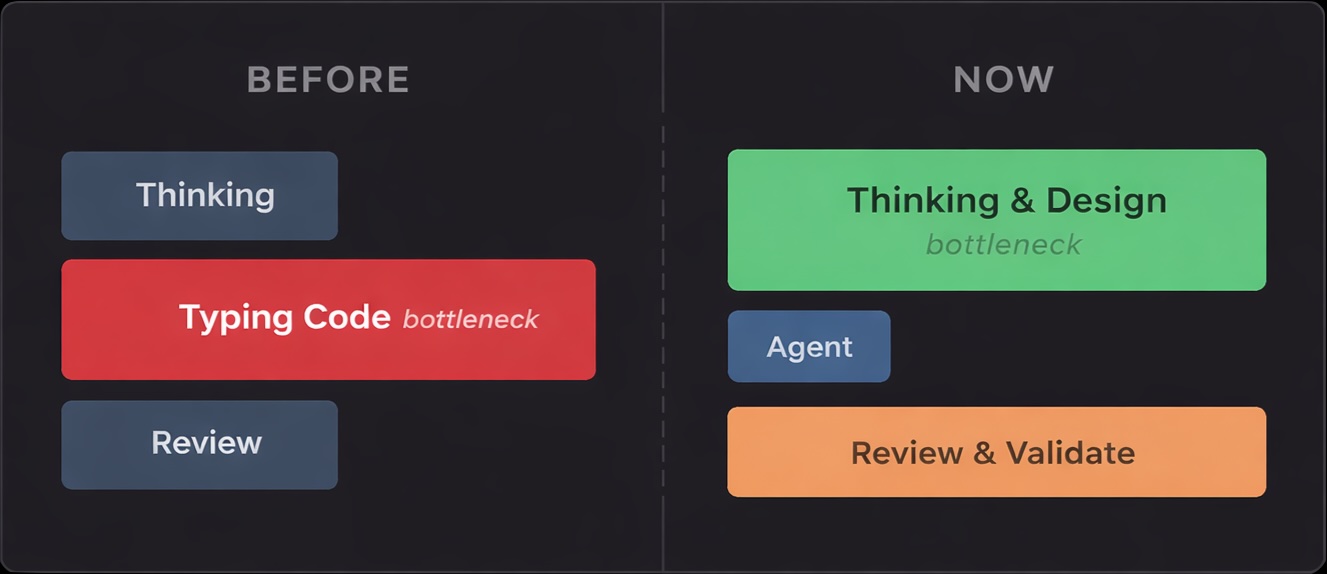

Typing Was Never the Job

Here’s something nobody told you in university: typing code was always a waste of time.

Think about it. CS programs teach algorithms, data structures, system design, discrete math. They don’t teach you to type faster. Why? Because typing was never the core skill. It was just… overhead. A necessary friction between the idea in your head and the running system.

We figured this out decades ago. Assembly programmers wrote one line per CPU instruction. Then we invented higher-level languages where a single line compiles into hundreds of instructions. Then we added frameworks, libraries, ORMs - each layer letting us type less while doing more. The entire history of programming is a march toward typing less. Agents are just the next step.

The best engineers I’ve worked with aren’t fast typists. They’re fast thinkers. They spend more time at whiteboards, in design docs, reading existing code - and less time with their fingers on the keyboard. The typing part was always the easy part. The thinking was hard.

Agents just made this obvious.

Agents are extremely good at the mechanical parts of coding:

- Writing boilerplate

- Refactoring across files

- Navigating large codebases

- Applying patterns consistently

They’re bad at:

- Knowing what to build

- Understanding why something matters

- Making trade-off decisions

- Recognizing when requirements are wrong

The bottleneck moved. It used to be typing. Now it’s thinking.

This has a practical implication: the few minutes you spend thinking before opening an agent session will save hours of cleanup. The agent will happily generate 500 lines of code that solves the wrong problem. Faster.

You’re the Tech Lead Now

Agents don’t replace developers. They behave like very fast, very junior, very confident engineers who never push back, never ask clarifying questions, and never tell you your requirements are wrong.

Sound familiar? That’s a junior dev who needs supervision. Except this one types at 10,000 words per minute.

Your job changed. You now:

- Define intent and scope

- Break down work into digestible pieces

- Review outputs critically

- Correct direction when it drifts

- Make judgment calls the agent can’t

That’s tech lead work. Every developer working with agents is now managing a tireless but context-blind junior. The question isn’t whether you can code faster - it’s whether you can think clearly enough to direct that speed productively.

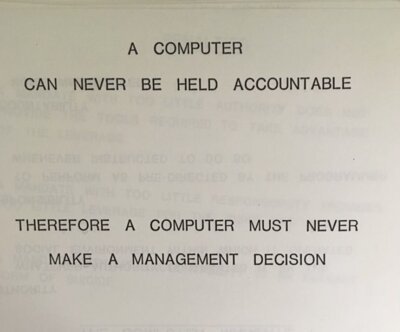

There’s an old IBM training slide from 1979:

Replace “computer” with “agent” and nothing changes. Agents are tools, not authors. You’re still accountable for what gets committed.

This matters because agents are genuinely bad at things that require judgment:

- Understanding product intent (why are we building this?)

- Evaluating architectural tradeoffs (is this the right abstraction?)

- Recognizing non-obvious constraints (will this scale? Is this secure?)

- Considering long-term consequences (how will this affect the codebase in a year?)

They optimize for local correctness and surface-level patterns. They’ll write code that compiles, passes the tests you gave them, and completely misses the point.

Human judgment remains irreplaceable: defining what matters, rejecting wrong-but-working solutions, keeping systems coherent over time. AI makes it trivially easy to produce code you don’t understand. This is technical debt in its purest form - you’ll pay for it during debugging, maintenance, and every code review.

“Won’t this destroy code quality?” Only if we let it. Agents don’t remove responsibility - they concentrate it.

Work in Phases, Not Prompts

Here’s the mistake most people make: they treat agents like a chat interface. Type a prompt, get code, paste it somewhere. That’s not agentic coding. That’s autocomplete with extra steps.

Real agentic work is phased. You don’t write a novel in one sentence, and you don’t build software in one prompt. The phases matter because they force you to think before generating, and because agents perform dramatically better when you separate concerns.

The four phases:

1. Problem Definition

Before touching any code, clarify what you’re actually building. This happens in a separate conversation or an explicit “planning mode.”

1

2

3

4

5

6

I need to implement [feature]. Here's the context:

- Current state: [what exists]

- Requirements: [what it should do]

- Constraints: [performance, compatibility, security]

What are my options? What trade-offs should I consider?

This phase is cheap. A few minutes of thinking. The agent helps you explore the problem space, surface edge cases you hadn’t considered, identify risks early. No code written yet.

2. Design Refinement

Once you have options, interrogate them. Push back. Ask hard questions.

1

2

3

4

Option B looks promising. But:

- How would this handle [edge case]?

- What's the failure mode if [scenario]?

- How does this integrate with [existing component]?

This is iterative. The agent proposes, you challenge, it refines. Still no implementation. You’re building a mental model and a shared understanding of what “done” looks like.

3. Implementation

Only now do you write code. And critically - you write it with explicit constraints from the previous phases.

1

2

3

4

5

6

Let's implement the approach we discussed. Starting with [component].

Key decisions we made:

- [Decision 1]: [rationale]

- [Decision 2]: [rationale]

Do not deviate from these without asking first.

The agent has context. It knows what you decided and why. It’s not guessing anymore.

4. Review & Validation

Never accept generated code blindly. Review the diff. Run the tests. Verify it actually does what you discussed.

This is also where testing happens. Some prefer test-driven development - writing tests before implementation. Either way, you need to be explicit with agents about testing:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Write tests for [component]. Specifically:

- Test [happy path scenario]

- Test [edge case 1]

- Test [error handling scenario]

- Mock [external service] - don't hit real endpoints

- Use real [database/cache] - no mocking for integration tests

- Do NOT test [implementation details that might change]

Agents will happily generate 50 tests that all test the same thing, or mock everything including the code you’re actually trying to verify. Be specific about what to test, how to test it, what to mock, and what should stay real.

This is where most time savings evaporate if you skip phases 1-3 - you end up debugging code you don’t understand that solves a problem you didn’t fully define.

These phases aren’t bureaucracy. They’re how you turn a chaotic code generator into a reliable collaborator. Skip them and you’ll spend more time fixing agent output than you saved generating it.

Prompts Are Contracts

Prompting is API design, not conversation.

Think about what makes a good API: clear inputs, defined outputs, explicit constraints, predictable behavior. Bad APIs accept anything and return surprises. Good APIs are strict about what they accept and consistent in what they return.

Same with prompts. “Fix this bug” is a bad API - undefined input, no constraints, unpredictable output. “This endpoint returns 500 when the user ID is null. Here’s the error log and the handler code. What’s causing this and what are my options?” is a good API - scoped input, clear context, defined expectation.

The difference in output quality is dramatic. Vague prompts produce vague code. Specific prompts produce specific solutions.

A few principles that help:

Scope aggressively. Don’t let agents roam freely across your codebase. Tell them exactly which files to touch and which to leave alone. “Modify only src/handlers/payment.ts” beats “fix the payment flow.” Smaller blast radius means easier review and fewer surprises.

Make constraints explicit. Agents don’t know your conventions unless you tell them. “Use our existing error format from src/errors.ts” or “Don’t add new dependencies” or “Keep the public API unchanged.” These aren’t obvious to an agent looking at your code for the first time.

Define what done looks like. “Implement caching” is ambiguous. “Add Redis caching for the /users/:id endpoint with 5-minute TTL, using our existing Redis client in src/infra/cache.ts” is actionable. The agent can verify its own work against concrete criteria.

Separate concerns. Avoid implementation and tests in the same prompt. The agent will write tests that pass its own code - which tells you nothing. Generate code, review it, then separately ask for tests with explicit guidance on what to cover.

“What about security?” Same as any automation. Scope, permissions, review. The danger is pretending agents are harmless because they feel conversational.

The Agent Instructions File

The instructions file (AGENTS.md, CLAUDE.md, .cursorrules, etc.) is the single most impactful thing you can optimize. This file affects every interaction the agent has with your codebase. A well-crafted file multiplies the effectiveness of every prompt you write.

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Keep it short and scannable | Write walls of text |

| Be specific and actionable | Use vague guidance |

| Explain why behind rules | Just list rules without context |

| Update it constantly | Set and forget |

| Focus on this repo’s specifics | Repeat generic coding standards |

Global Instructions

You should define global instructions that apply across all your projects - personal preferences, coding style, behavioral defaults. These are “how I work” regardless of what codebase I’m in.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

# Global Instructions

## Communication Style

- Write as if talking to a peer engineer

- Avoid filler, hype, or disclaimers

- Ask for clarification when context is ambiguous

- Don't restate the obvious

## Coding Conventions

- Keep code clean and modular, but aim for simplicity

- Add comments only for unusual logic or rationale

- Always include type annotations

- Assume every project has linter and styling rules

## Architecture Principles

- Prefer composition over inheritance

- Use dependency injection for testability

- Adhere to SOLID principles

## Behavioral Defaults

- Prefer compact answers unless detail is essential

- When adding tests, always find a way to run them

- Keep documentation in sync with code changes

Project Instructions

Project files layer specifics on top - “how this codebase works.”

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

# Project: my-service

Backend service handling payment processing.

**Tech Stack:** Node.js 22.x, TypeScript, Express, PostgreSQL

## Development Setup

npm install

docker-compose up -d # starts Postgres

npm start # runs on port 4024

## Testing

npm test # runs all tests (requires Postgres)

npm test -- path/to/file.spec.ts # single file

## Architecture

### Entry Points

1. **REST API** - Handler: `apiHandler`

2. **Event Consumer** - Handler: `eventProcessor`

- Trigger: SQS messages from `payments-queue`

### Key Patterns

- All handlers use dependency injection via constructor

- Database access only through repository classes

- External API calls wrapped in circuit breakers

## Conventions

- Error responses use RFC 7807 format

- All amounts stored as integers (cents)

- Timestamps in UTC, ISO 8601 format

Treat both as API contracts for agents. Changes should be intentional and reviewed, just like code.

Context Management

A critical insight: context degradation begins around 70% usage, not at 100%. Long conversations lead to:

- Forgotten earlier instructions

- Contradictory suggestions

- Repeated mistakes you already corrected

- Declining code quality

Signs your context is degraded:

- Agent forgets constraints you stated earlier

- Suggestions contradict previous decisions

- Quality noticeably drops from earlier in the conversation

- Agent starts “looping” on the same approaches

Strategies

1. Scope Conversations Tightly

One task per conversation. Don’t let sessions sprawl across unrelated concerns.

- Good: “Implement the payment validation endpoint”

- Bad: “Let’s work on the payment service” → then drift through five different features

2. The Copy-Paste Reset Technique

When context is degraded but you have useful progress:

- Ask the agent to summarize the current state, decisions made, and remaining work

- Start a fresh conversation

- Paste the summary as your opening context

- Continue with a clean context window

This gives you the benefits of accumulated progress without the degradation.

3. Use External Memory

Don’t rely solely on conversation history. Externalize important decisions:

- Update your instructions file with new patterns or constraints discovered during work

- Maintain a scratchpad file for complex multi-step tasks

- Document architectural decisions in your design docs

When You’re Stuck

If you find yourself:

- Asking the same question multiple ways

- Getting similar unhelpful responses

- Watching the agent repeat the same mistake

- Feeling frustrated with the output

You’re in a loop. Don’t keep iterating - change your approach.

Breaking Out:

Clear and Restart - Start a fresh conversation. Rephrase your goal from scratch. Often the accumulated context is the problem.

Simplify the Problem - Can you solve a smaller version first? Can you isolate the confusing part? Are you asking multiple things at once?

Show, Don’t Tell - Instead of explaining what you want, show an example. Provide a working snippet and ask for something similar.

Reframe the Problem - Instead of “how do I fix X” → “what are the possible causes of X”. Instead of “implement feature Y” → “what’s the simplest way to achieve Y given these constraints”.

Change Tools - Different LLMs have different strengths. If one isn’t working, try another.

The Title, Revisited

Agents are fast. That part is obvious now. They’ll generate code faster than you can read it, refactor entire modules in seconds, and never complain about tedious tasks.

But speed without direction just gets you lost faster.

The title of this post isn’t “Agents are fast, isn’t that great?” It’s “Agents are fast. You’re responsible.” The period matters. These are two separate statements. The first is a fact about the tool. The second is a fact about you.

Everything I’ve described - the phases, the contracts, the instructions files, the context management - exists to bridge that gap. To turn raw speed into directed progress. To ensure that when code hits production, someone understood it, validated it, and chose to ship it.

The tools will keep getting better. The models will keep improving. What won’t change is accountability. You’re still the engineer. You still own what gets committed. The agent is just a very fast, very eager collaborator that needs clear direction and constant supervision.

Use that speed wisely.