Technical Design Documents

Design docs get a bad rap. Some teams treat them like bureaucratic overhead, others like sacred scripture that must be followed to the letter. Both miss the point.

The real purpose of design documentation isn’t uniformity or process compliance. It’s about articulating, sharing, and refining ideas before you start writing code. Whether that’s a 10-page spec or a whiteboard sketch - the format matters less than the thinking it forces you to do.

These documents - whether a brief outline, a structured specification, or simply a whiteboard sketch - serve to capture core objectives, constraints, and anticipated challenges early on. This proactive approach improves alignment, reduces misunderstandings, and ultimately increases the quality of the end product.

Why Bother?

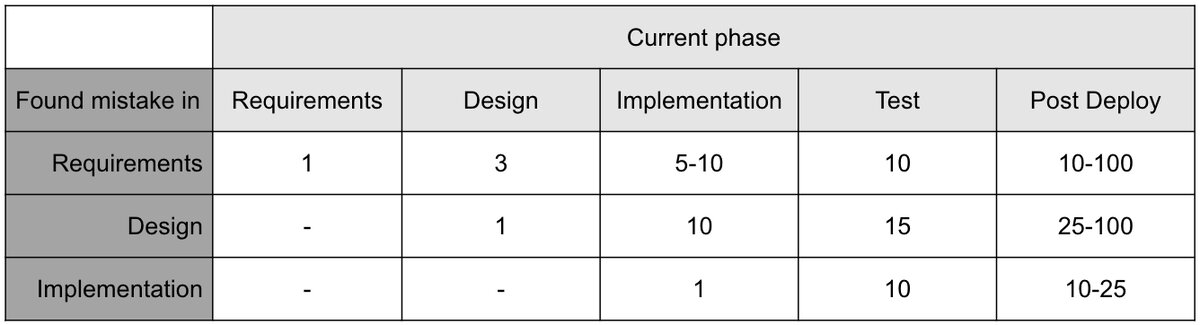

The cost of fixing mistakes grows exponentially as a project moves through its lifecycle. Code Complete famously illustrates this with the “cost of mistake” curve:

A requirements mistake caught during requirements costs 1x to fix. Catch it post-deploy? That’s 10-100x. Design mistakes follow a similar pattern. Design documents act as an early safeguard - catching issues before they multiply in cost and complexity. Nothing fancy here.

When to Write One

Not every task needs a design doc. Here’s when it actually helps:

1. New Features or Major Enhancements. Documenting the design clarifies functionality, dependencies, and architectural impact. The trigger is obvious, but some folks skip this step and regret it later.

2. Complex Dependencies or Cross-Team Integration. Features that touch multiple teams or rely on external systems need extra clarity. A design doc helps map out dependencies, integration points, and cross-functional impacts. Reduces last-minute surprises.

3. Significant Refactoring. Major refactoring efforts - especially those impacting core architecture or shared components - benefit from documented objectives and anticipated outcomes. It also lets teammates discuss alternative approaches before anyone writes code.

4. Technical Challenges and Unknowns. POCs, feasibility studies, creative problem-solving under constraints. A design doc becomes a platform to hypothesize solutions, evaluate feasibility, and gather feedback. Particularly valuable when choosing between multiple approaches.

5. High-Impact or Customer-Facing Changes. Anything that directly impacts user experience or has high bug risk. Design documentation helps anticipate issues and evaluate risks upfront.

When to Skip It

Sometimes the design you create in your head is enough. What matters is that you’ve thought through the approach before diving in.

Design docs are overhead. If the task is small, well-understood, and unlikely to benefit from broader discussion, skip the doc. For trivial fixes, minor tweaks, or isolated refactoring - just write good comments in your code explaining the reasoning.

When it reads like an implementation manual. If your design document feels like step-by-step instructions, stop. Break the work into tickets instead. Design docs should focus on “what” and “why”, not granular “how”.

Known problems. For routine problems already solved repeatedly in similar ways, just refer to existing templates or past solutions. Don’t duplicate effort.

Types of Design Documents

Three practical options:

1. High-Level Overview. For early brainstorming or stakeholder alignment. Captures main goals, constraints, and basic technical direction. No formal structure needed - its purpose is capturing and communicating key ideas. This is probably the most common type. Typically 3-7 pages, balancing clarity and detail. Good enough for most scenarios.

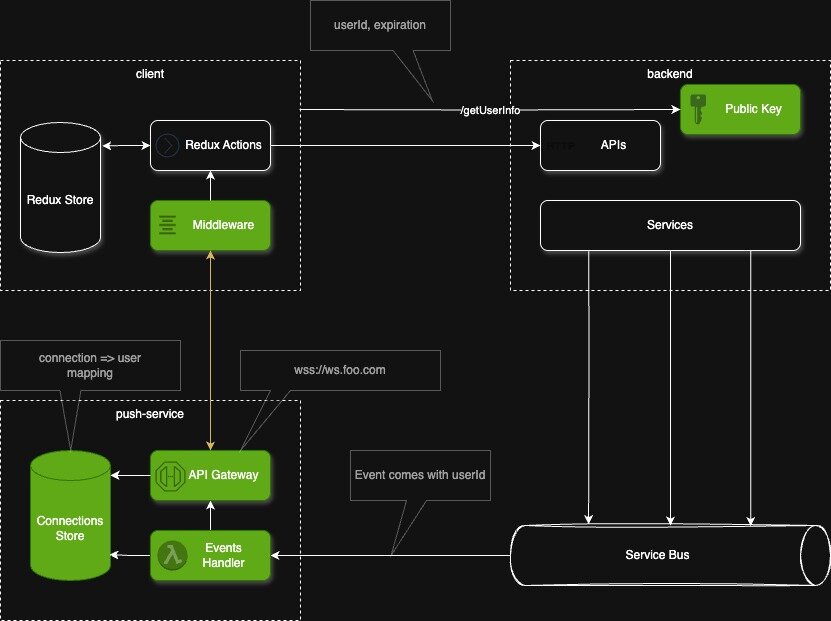

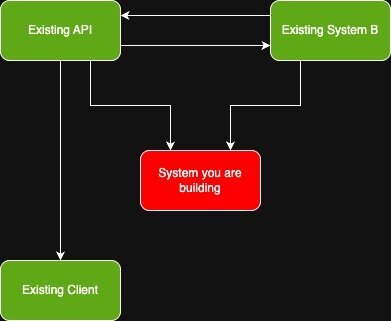

2. Detailed Design Specification. When technical depth or cross-team coordination is essential. Includes specific functional requirements, architectural considerations, and diagrams for complex data flows. Follows a more formal structure.

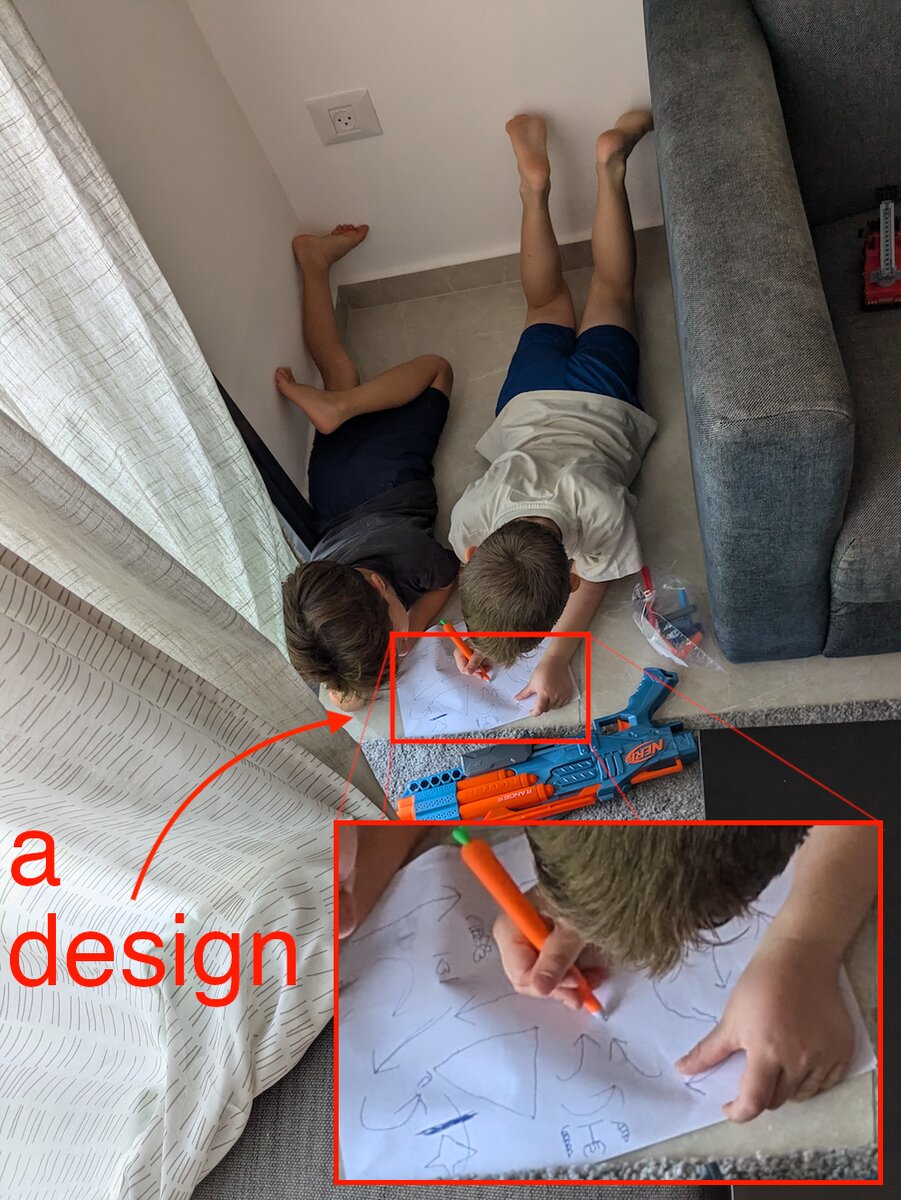

3. Whiteboard Sketch or Quick Diagram. Sometimes a photo of a whiteboard is all you need. Great for simple tasks or ideation sessions. Less formal but effective for getting ideas across quickly.

💡 The goal is to make documenting your design simple and approachable. Choose the type that fits your needs. There’s no rigid template.

Writing Good Design Docs

Start with the Problem. A good design document starts with a clear articulation of the problem, the context, and why it matters. If product requirements exist, translate them into technical terms:

- Product Requirement: “Users should be able to see their recent transactions instantly.”

- Technical Problem Statement: “Design a low-latency API and caching strategy to retrieve and display recent transactions within 200ms.”

Clarity Over Perfection. A design doesn’t need to be perfect - it needs to be understandable. Focus on communicating core ideas, key decisions, and trade-offs. Use simple terms and visualize whenever possible, even if you feel uncomfortable drawing. Diagrams and flowcharts often communicate complex ideas more effectively than text.

Provide a High-Level Overview. Focus on which parts of the system will be created or modified and how they relate to each other. Prioritize logical relationships over technical details like protocols or database types.

It’s also valuable to include a System Context Diagram showing how the solution fits into the overall platform:

Document Key Decisions and Trade-offs. A design isn’t just about “what” you’re building but also “why”. Capture the reasoning behind major decisions, including alternatives you considered and why you rejected them.

For example:

- Decision: Cache the last 50 transactions per user in an in-memory store

- Trade-off: Improves API response time but introduces stale data risk if cache invalidation is delayed

- Alternative Considered: Query database directly for each request. Rejected due to performance degradation under heavy load.

💡 Every decision involves a trade-off. Capturing these ensures transparency and avoids revisiting the same discussions later.

Consider Your Audience. Some designs are reviewed by deeply technical teammates. Others need to be presented to product teams or stakeholders with minimal technical background. Tailor accordingly.

Iterate. Don’t aim for a complete final document on your first try. Begin with a rough draft, refine based on feedback. Share for feedback once the main idea is communicated clearly - not while it’s half-baked. Think through potential challenges reviewers may raise and address them preemptively.

Design documents are living artifacts. Update them as the project evolves or new decisions are made. They should remain a reliable source of truth throughout the project lifecycle.

References

Books and Articles

- Code Complete by Steve McConnell - practical advice on software construction

- Designing Data-Intensive Applications by Martin Kleppmann - system design challenges and trade-offs

- Martin Fowler’s Architecture Decision Records - documenting architectural decisions effectively

Online Resources

- System Design Primer (GitHub) - system design resources and examples

- AWS Well-Architected Framework - best practices for scalable cloud systems

- Google’s Site Reliability Engineering Guide - engineering reliable systems

Diagrams and Visualization Tools

- Lucidchart, draw.io, WebSequenceDiagrams - clear, shareable visuals

- C4 Model - lightweight approach to architecture diagrams focusing on clarity and hierarchy

Case Studies

- Uber Engineering Blog - large-scale system design challenges

- Netflix Tech Blog - architectural patterns and trade-offs at scale

- High Scalability - real-world architectural examples